Print  |

|

Tolkien’s Elvish

Posted by Thorsten Renk on July 16, 2011

Thorsten Renk is a theoretical physicist working at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland. He has written introductory courses for Sindarin and Quenya.

A whole family of languages with a single native speaker !

J.R.R.Tolkien is chiefly known as author of ‘The Hobbit’ and ‘The Lord of the Rings’ and the creator of Middle-Earth, but his ‘secret vice’ was the creation of languages. As he puts it himself:

The invention of languages is the foundation. The ‘stories’ were

made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse.

To me a name comes first and the story follows. (Letters p219)

While there are relatively few names and Elvish sentences in his published novels, there exists a large body of notes describing the various Elvish languages in some detail which has been published chiefly in special-interest journals in recent years. But Tolkien did not only invent Quenya, Sindarin, Telerin and other Elvish, Dwarvish and Mannish languages – he invented a whole history to explain how all these languages arose from common roots, changed over time according to different rules giving the languages their individual flavours and later acquired loan-words.

How does one create a language?

To some degree, all these invented languages are influenced by real languages.

This has its origin in Tolkien’s ideas of aesthetics – he deliberately wanted to create, for example, a Welsh-themed language (which then became Sindarin), a Finnish-Latin themed language (Quenya) and experimented with a Hebrew-flavoured language (Adûnaic). But the similarity is more in grammar and phonetics than in the actual borrowing of words, and his languages are genuine inventions, rather than copies of existing languages.

A history in two-dimensional time

How many Elvish laguages are there all together? That’s difficult to say, because unlike real languages, Tolkien’s Elvish has a history in real and imaginary time.

In real time, we can trace how Tolkien’s ideas evolved from the earliest manuscripts around 1916 to his works more than 50 years later and can observe for example the Welsh-themed Elvish language change from Goldogrin (Gnomish) to Noldorin and finally Sindarin.

At the same time, along with Middle-Earth, the languages all have a history – there is an Old Sindarin that is the ancestor in imaginary time of the Sindarin used in ‘The Lord of the Rings’ just as Goldogrin is an ancestor in real time.

Can one speak Elvish?

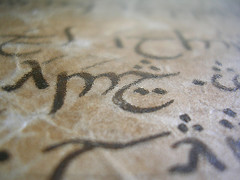

No one was ever fluent in Elvish to the degree that he could hold a longer conversation in Elvish – not even Tolkien was a fluent speaker! Tolkien’s interest was the aesthetics of language creation and the use of them in his stories – thus, Elvish primarily exists as a written language.

The early languages are fairly well developed – Goldogrin has about 7000 words and we know a lot of its grammar for instance.

Of the languages used in ‘The Lord of the Rings’, Quenya with about 2000 words and Sindarin with perhaps 1200 words are the most developed and can be used to translate poetry or even prose texts, while Telerin with less than 300 known words is already marginally usable only. Some other forms of Elvish are known mostly on a theoretical level – for instance, of Avarin only six words are attested.

Scholars and inventors – the modern Elvish community

Especially sparked by the Elvish texts used in the ‘Lord of the Rings’ movies, there is a community of Elvish enthusiasts around the world which keeps the languages alive and in use. Somewhat unfortunately, the community is divided into people interested in a scholarly analysis of Tolkien’s manuscripts and others interested in making Elvish usable by inventing new words if needed, with very little overlap between the groups.

A small group of scholars (the so-called editorial team) is directly tasked by Christopher Tolkien to publish the remaining manuscripts over time.

Based on these commented and referenced publications in the journals Vinyar Tengwar and Parma Eldalamberon, a larger group of people works on a detailed understanding of Tolkien’s ideas and their change over time. These people write summaries and overview articles (and even language courses), which are then used by Middle-Earth enthusiasts, life roleplaying gamers or poets to learn and use the Elvish languages.

The people desiring to make Elvish a usable language contend that languages are living, changing things, not to be displayed as unchanging entities in a museum.

On the other hand, the proponents of the scholarly approach reply that things are not so simple – first, the usual rules of language change do not apply when the (fictional) native speakers are immortal. Second, all attempts to construct unified Elvish grammar or vocabulary in the past have been discovered to be characterized by an artificial regularity.

For Tolkien, the story is always linked with the languages, and Elvish reflects this essential link in almost every bit of vocabulary – a fact which possibly makes it quite unique among languages, but makes it very hard to extend and use without destroying its essential ‘Elvish-ness’.

Leave a comment

No Comments »

No comments yet.